Hand position and the extraction of the blade

To extract the blade from the water is not a trivial thing as every rower knows and certain hand positions make extracting the blade more difficult than is necessary.

This text is a reaction to the technique taught by some rowing instructors in my home-country, Holland. They teach pulling the handle ‘with a flat hand’ to beginning rowers, and I have seen the same instruction in a Rowperfect newsletter some time ago.

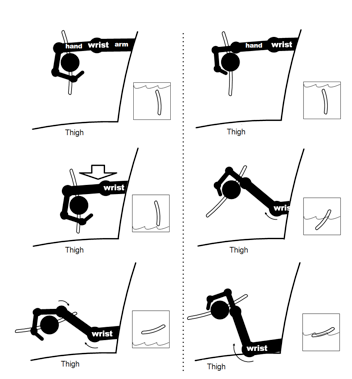

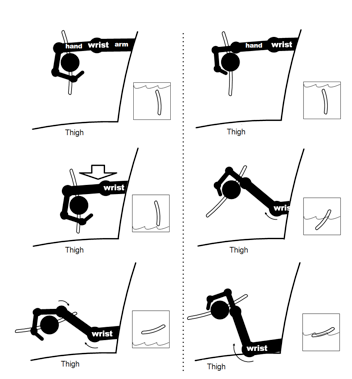

With the phrase ‘with a flat hand’ these instructors not only mean ‘with a flat wrist’, but ‘with a flat wrist and flat knuckles’, which means the handle is to be pulled with the tips of the fingers. This leads to several difficulties in rowing: application of force with the fingertips is limited, even after strength training and the hand does not have a stable position with regard to the handle, but the biggest problem emerges approaching the finish of the stroke. Since the hand can not be opened any further, feathering the blade in this position can only be done by flexing the wrist back over 90o, as can be seen in the drawing. Flexing the wrist this far is in itself a challenge to many, but the main problem is that most people do not have enough room between handle and thigh to accommodate for a full hand palm’s length. Anticipating this lack of room they do not even try to make a clean extraction and the result is that the blade sticks heavily to the water after a partial extraction and feathering; this may feel safe to beginners so the problem is not recognized or is even cherished. The problem surfaces only much later, when they start rowing with experienced rowers and even then the problem often is not recognized.

The solution is to grab the handle with a full firm grip, the knuckles flexed at about 70o. Feathering now becomes a combination of an easy 20-40o wrist flexion, combined with an opening of the hand’s grip to complete the 90o rotation of the handle. As this leaves ample room below the handle a clean extraction (before feathering) now is an easy thing.

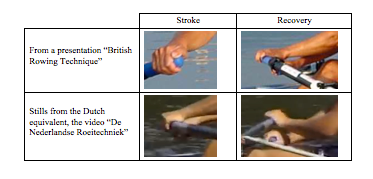

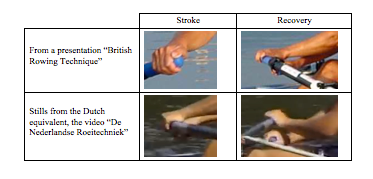

The drawing shows the extraction of the blade, using two different hand positions. I do not think the hand position on the right side is an exaggeration of what I have regularly seen. There are also some pictures from british and dutch instruction material.

Other things can be said about hand positions but I just wanted to focus on this sometimes controversial aspect.

Bert Hoefsloot, a reader from the Netherlands kindly wrote this coaching advice to help others teach the extraction of the rowing or sculling blade.

Oktober 2014

This Post Has 3 Comments

I disagree.

Your analysis assumes the blade handle remains “stuck” to the fingers in the exact same position throughout the stroke. With a flat wrist and light grip, the blade actually rolls through the fingers. The motion is similar to rolling a broom handle along a table by opening and closing ones hand in an inch worm fashion.

Some further comments. This analysis is not correct from either a mechanical point nor for rowing performance.

There is a picture of an example of both techniques at:

https://www.rowperfect.co.uk/grip-in-rowing-a-controversial-suggestion/

From a mechanical point, stresses should be applied in a straight line, either tension or compression. Otherwise the stress is applied as a bending load, and materials need to be stronger when resisting bending loads rather than tension/compression.

Look at the oar handle position when gripping the oar with the fingers wrapped around the oar and the thumb underneath (the more conventional grip). The center line of the oar is under the line connecting the hand/wrist/forearm/arm. This introduces a bending load when pulling on the oar which has to be resisted by extra force by the oarsman. This subtracts from the total force that the oarsman can apply to the oar.

When I row with straight fingers, the oar/wrist/forearm/arm forms a more nearly straight line, which is theoretically more efficient.

Also, the oar is now 2-5 cm further away from my body. This either gives me a longer stroke or, for the same length of stroke, allows me to not come as far forward at the catch which puts my body in a stronger position at the catch or allows me to not lay back as far at the release, which is also mechanically more efficient.

With the oar further away from my body, the inboard arm does not have as much a bend in it, which makes it stronger the entire stroke.

(Sculling boats are 2-3% faster than sweep boats, which is 6-9% more effective power. Both scullers arms are straight most of the stroke, whereas the sweep rower has a bent (semi-crippled) inboard arm. Thus, the sculler puts more of their power into the blade.)

All this is nice in theory, what about reality? Recently, our club had some erg trials. One rower was 10+ sec/500m faster than me (my excuse is that he is 30+ years younger). We were bow pair in our 8+ with Smart Oars for the two of us, and recorded a 500+ meter piece. The recorded data showed we were rowing with virtually identical force. So, my reduced power as measured by the erg seemed to be applied more efficiently as measured by the force curve at the oar. Take this sample size of one with the appropriate number of grains of salt.

The straight finger grip may not be suitable for some/many/most rowers since it requires substantial finger strength. I can dead lift more than 2X BW with a straight grip. The peak and average force measured on the RP3 and ErgData on the Concept2 are much less than that, so I have never had a problem. This grip is race proven now for more than a year.

Sculling with this straight finger grip is even more technically challenging. The thumb has to supply both lateral location and feathering torque. The wrist is not that much involved, remaining more in line with the oar and arm. I have developed interesting new callouses the times that I scull with this.

Use the feather to drive the boat!

Two things have to happen at the finish. The blade has to leave the water, and be feathered.

Try this!

Start feathering as the upper edge of the blade reaches the surface. Use enough rotating force to push water away, but NOT lift it. The blade should continue to be pulled and rotate about the gate until the feathering is complete, and the flat blade just clear of the water.

The modern blades have a larger area below the shaft, and this will give you more water pushed during the feather.

Any water pushed back will help drive the boat.

It is interesting that many scullers seem to feather as the blade is lifted, although I have seen no suggestion that it is done to drive the boat.

I also suggest the following: Legs and arms finish TOGETHER. Hands immediately away to clear the rebounding knees. NO pausing!! Two Breaths – out at the catch and release. 1:1 in:out always, at 25+ spm. Arms only straightened at the catch. Layback at the catch by rotating above the hips. The ‘Rhecon’ style.

Have fun.